The Impact of Vitamin D Deficiency on Cognitive and Neuromuscular Functions in Elderly Patients

Keywords

Abstract

Background/Aims:

Vitamin D plays an important regulatory role in neuronal and neuromuscular signalling, partly through its effects on calcium homeostasis, neuroinflammatory pathways, and vitamin D receptor–mediated transcription in neurons and glial cells. Deficiency of vitamin D is common among older adults and has been associated with impaired cognitive performance, reduced neuromuscular function, and elevated inflammatory activity. However, its relationship with neurocognitive and neuromuscular signalling deficits in aging populations remains insufficiently characterized. To investigate the associations between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D [25(OH)D] levels, cognitive performance, neuromuscular function, and inflammatory signalling markers in older adults, and to explore whether altered calcium metabolism or inflammatory activation may contribute to these functional impairments.Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted over six months (March–August 2025) at Tikrit Teaching Hospital, enrolling 250 adults aged 65–85 years via systematic random sampling. Cognitive function was assessed using the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA). Neuromuscular performance was evaluated by handgrip strength, gait speed, Timed Up and Go (TUG) testing, bioelectrical impedance analysis, and electromyography (EMG) to detect abnormalities in neuromuscular transmission. Serum 25(OH)D, calcium, phosphorus, parathyroid hormone (PTH), alkaline phosphatase, creatine kinase, C-reactive protein (CRP), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) were measured. Associations between vitamin D status and functional or biochemical outcomes were examined using Pearson correlations and group comparisons (p < 0.05 considered significant).Results:

Vitamin D deficiency was highly prevalent (62.0%), with 23.2% showing insufficiency and 14.8% sufficient levels. Lower 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with reduced MMSE and MoCA scores, weaker handgrip strength, slower gait speed, prolonged TUG times, decreased skeletal muscle mass, and a higher frequency of EMG abnormalities indicative of impaired neuromuscular signalling. Deficient participants showed significantly lower calcium and higher PTH, CRP, and IL-6 levels, reflecting disturbances in calcium regulation and heightened inflammatory signalling. Pearson correlation coefficients (r = 0.30–0.62) demonstrated moderate positive associations between 25(OH)D and cognitive and neuromuscular performance, and negative associations with TUG time and inflammatory biomarkers.Conclusion:

Vitamin D deficiency in older adults is associated with impaired cognitive function and neuromuscular performance, potentially mediated by dysregulated calcium signalling and increased neuroinflammatory activity. These findings support a mechanistic link between vitamin D status and neuronal as well as neuromuscular communication pathways. Longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to clarify causality and determine whether vitamin D optimization may help preserve neurocognitive and neuromuscular function in aging populations.Introduction

Vitamin D is a pleiotropic secosteroid hormone essential for maintaining calcium and phosphorus homeostasis and skeletal integrity, but it also exerts wide-ranging extra-skeletal effects, including the modulation of neuronal signalling, neuromuscular communication, immune responses, and brain function [1]. Its hormonally active form, 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D [1, 25(OH)₂D], acts through the vitamin D receptor (VDR), which is expressed in multiple organs involved in neurophysiology, such as the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, skeletal muscle, and immune cells [2]. Through VDR-mediated transcriptional regulation, vitamin D influences the expression of genes involved in neuronal excitability, neurotransmitter synthesis, synaptic plasticity, cell proliferation, and apoptosis. These broad regulatory actions highlight the growing interest in vitamin D as a potential modulator of neuronal and neuromuscular signalling, particularly in older adults.

Vitamin D deficiency is highly prevalent in aging populations due to reduced cutaneous synthesis, impaired renal hydroxylation, decreased outdoor activity, and dietary insufficiency [3]. Skin production of vitamin D₃ declines with age, and renal 1α-hydroxylase activity diminishes, limiting the conversion of 25(OH)D to its active form [4]. Limited sunlight exposure—often due to indoor living, cultural clothing styles, or mobility restrictions—further exacerbates deficiency [5]. Epidemiological evidence indicates that 60–80% of older adults worldwide have insufficient vitamin D levels, with even higher prevalence among the housebound or institutionalized elderly [6].

Beyond its well-established role in skeletal health, vitamin D has emerged as an important regulator of central and peripheral nervous system function [7]. VDR and 1α-hydroxylase are widely distributed across key brain regions—including the hippocampus, cortex, and cerebellum—suggesting that vitamin D participates directly in neuronal activity and signalling [8]. Experimental studies demonstrate that vitamin D enhances neurotrophic signalling (e.g., nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor), modulates neurotransmitter synthesis, reduces oxidative stress, and provides neuroprotection against amyloid-induced toxicity [9]. These mechanistic insights support the hypothesis that inadequate vitamin D may contribute to cognitive decline, neurodegeneration, and impaired synaptic communication in aging individuals [10].

Vitamin D is also integral to neuromuscular physiology. It facilitates calcium flux in muscle cells, regulates protein synthesis, and supports the maintenance of type II muscle fibers, which are critical for rapid and forceful muscular contractions [11]. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with reduced muscle strength, impaired balance, slower gait speed, increased fall risk, and higher prevalence of sarcopenia. Additionally, vitamin D influences neuromuscular junction stability and motor unit function, and deficiency may impair neuromuscular signalling indirectly through secondary hyperparathyroidism, systemic inflammation, and metabolic dysregulation [12].

Inflammation represents another mechanistic pathway linking vitamin D deficiency to neurocognitive and neuromuscular dysfunction. Vitamin D suppresses pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and C-reactive protein (CRP) while promoting anti-inflammatory mediators [13]. Chronic low-grade inflammation—a hallmark of aging—can exacerbate neuronal injury, disrupt synaptic transmission, accelerate muscle catabolism, and impair neuromuscular coordination. Elevated circulating IL-6 has been associated with poorer cognitive performance, reduced muscle strength, and greater functional decline. Therefore, vitamin D deficiency may amplify these age-related processes by permitting heightened inflammatory signalling [14].

Although numerous studies have examined the relationship between vitamin D status and cognitive or physical function in older adults, findings remain heterogeneous across populations. Meta-analyses support associations between low 25(OH)D levels and increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia, as well as diminished neuromuscular performance as reflected by handgrip strength, gait speed, and balance testing [15–17]. However, differences in ethnicity, lifestyle, sunlight exposure, and comorbidities contribute to variable outcomes.

Despite abundant sunlight, vitamin D deficiency is paradoxically widespread in Middle Eastern countries such as Iraq, where factors including cultural clothing practices, limited outdoor activity among older adults, air pollution, and restricted dietary intake contribute to inadequate vitamin D status [18]. Most regional studies have focused on bone health or cardiometabolic outcomes, leaving a notable gap in understanding how vitamin D levels influence neurocognitive and neuromuscular function in elderly Iraqis. Given that cognitive impairment and physical frailty are major determinants of disability, dependency, and reduced quality of life in older populations [19, 20], investigating signalling-related pathways that underlie these conditions is of clinical and public health importance.

The present study aims to evaluate the associations between vitamin D deficiency, cognitive performance, and neuromuscular function in older adults attending Tikrit Teaching Hospital and its outpatient clinics. A further objective is to examine whether alterations in biochemical markers—including calcium metabolism and inflammatory signalling—may mediate these functional deficits, thereby providing insight into the neurophysiological mechanisms linking vitamin D status to age-related decline.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

A cross-sectional analytical study was conducted at Tikrit Teaching Hospital and its

affiliated outpatient clinics in Tikrit, Iraq. Data collection took place over a six-month

period from March to August 2025. The primary objective was to examine associations between

vitamin D status and cognitive as well as neuromuscular function in older adults, with

particular attention to neurophysiological and inflammatory pathways. The study protocol was

approved by the Scientific Investigation Committee of the College of Medicine, Tikrit

University, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Study Population

A total of 250 male and female patients aged 65–85 years were enrolled using a systematic

random sampling strategy from medical, neurological, and geriatric clinics. Eligible

participants were required to be clinically stable and able to undergo cognitive and

physical assessments. Exclusion criteria included severe hepatic or renal impairment,

chronic vitamin D supplementation for more than six months prior to enrollment, active

malignancy, or acute infections, in order to minimize potential confounding effects on

vitamin D metabolism and neuromuscular function.

Data Collection and Clinical Assessment

Demographic and clinical data were collected using a structured questionnaire that included

age, sex, body mass index (BMI), educational level, medical comorbidities, medication use,

and lifestyle factors (including smoking status and sun exposure). Standardized physical

examinations assessed muscle tone, coordination, reflexes, and balance, along with blood

pressure, pulse rate, and anthropometric measurements.

Laboratory Investigations

Fasting venous blood samples were collected in the morning. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D

[25(OH)D] concentrations were measured using a chemiluminescent immunoassay (Abbott

Architect i2000SR). Additional biochemical markers—including calcium, phosphorus, magnesium,

parathyroid hormone (PTH), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and creatine kinase (CK)—were

analyzed using a COBAS INTEGRA 400 plus automated system (Roche Diagnostics). Inflammatory

markers included C-reactive protein (CRP) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Serum creatinine (Cr)

and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) were also measured to evaluate renal

function, given its role in vitamin D hydroxylation.

Cognitive and Neuromuscular Assessment

Cognitive performance was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) and

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), both validated tools for screening cognitive

impairment in older adults. Neuromuscular function was evaluated using handgrip strength

(Jamar digital dynamometer), gait speed over a 4-m walkway, and the Timed Up and Go (TUG)

test to assess dynamic balance and mobility. Muscle mass and body composition were measured

using bioelectrical impedance analysis (InBody 270). Electromyography (EMG) was performed in

a subgroup of participants to detect abnormalities in neuromuscular transmission and motor

unit activation patterns, providing insight into potential signalling deficits. Cognitive

and neuromuscular assessors were not blinded to participants’ vitamin D status due to

standard clinical workflow constraints; however, assessments followed strict standardized

protocols to minimize potential bias.

Statistical Analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Quantitative variables were presented as means ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical

variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Group differences across vitamin D

status categories were compared using independent samples t-tests or one-way analysis of

variance (ANOVA) as appropriate. Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess

associations between serum 25(OH)D levels and cognitive, neuromuscular, and biochemical

indices. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.3.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

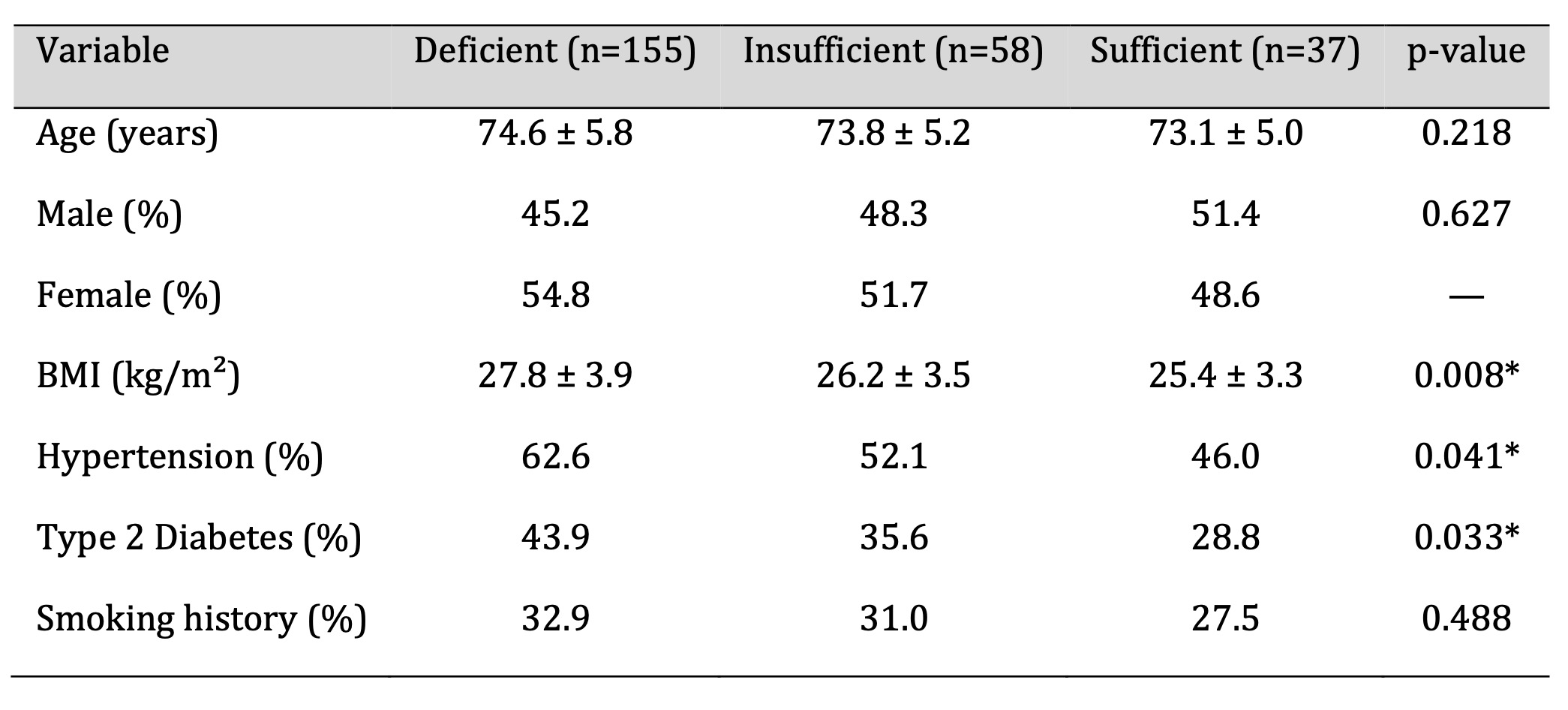

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population.

Vitamin D deficiency was more frequent in females (54.8%) than in males (45.2%). Individuals

with deficient vitamin D levels exhibited a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity,

hypertension, and diabetes compared with those classified as vitamin D sufficient (p <

0.05). These findings suggest that metabolic comorbidities were more common among

participants with lower 25(OH)D concentrations.

Table 1: Demographic and Clinical Attributes of the Study Cohort. Significant at p < 0.05

Biochemical and Inflammatory Markers

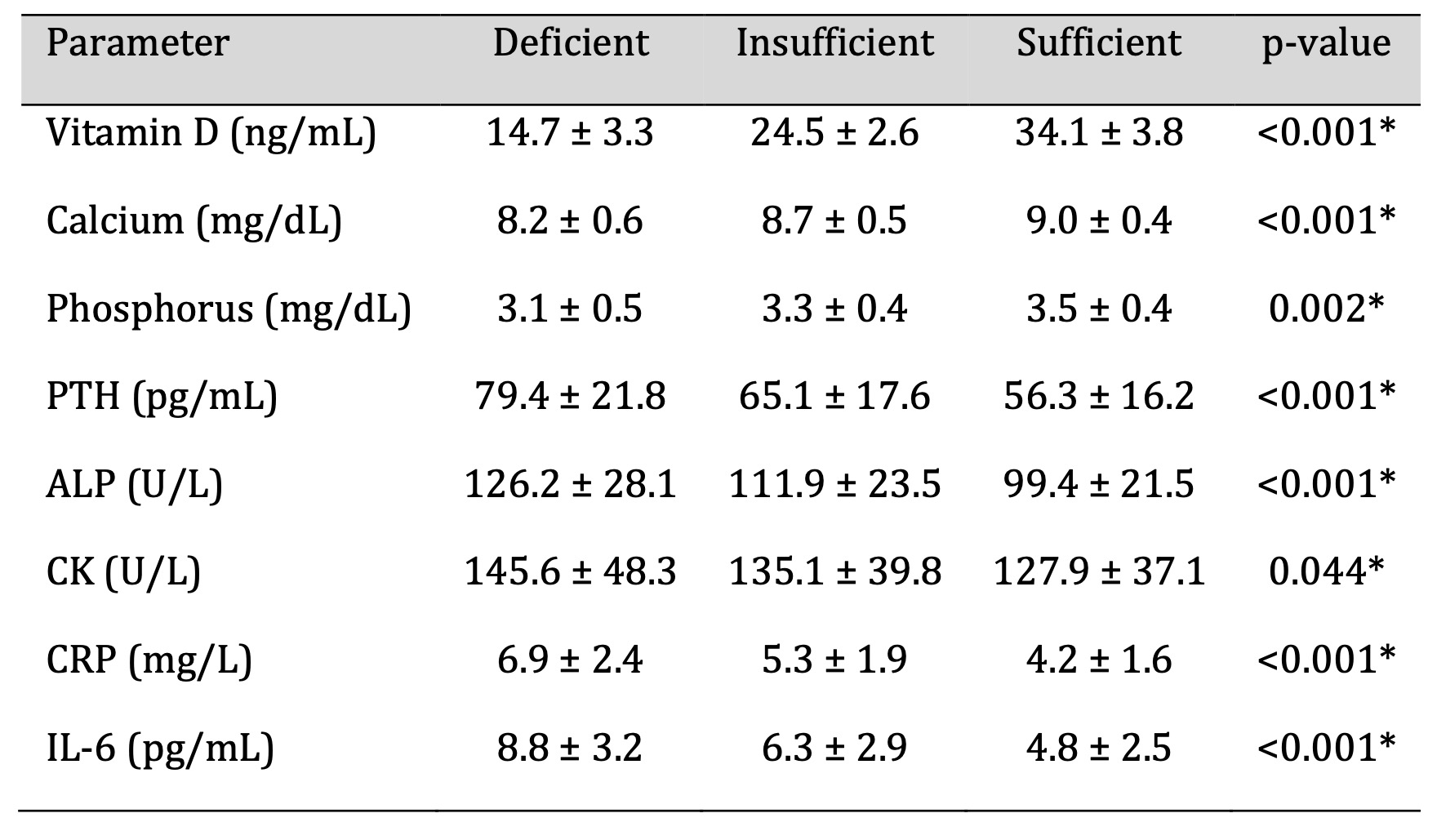

As shown in Table 2, serum calcium levels were significantly lower in participants with

vitamin D deficiency, whereas parathyroid hormone (PTH), C-reactive protein (CRP), and

interleukin-6 (IL-6) concentrations were markedly higher compared with vitamin

D–sufficient

individuals (p < 0.001). The observed biochemical profile is consistent with

secondary

hyperparathyroidism and elevated inflammatory signalling activity. These alterations

reflect

disturbances in calcium regulation and systemic inflammation associated with low 25(OH)D

levels. Although causality cannot be inferred, the pattern suggests that dysregulated

calcium homeostasis and heightened inflammatory pathways may contribute to the cognitive

and

neuromuscular impairments observed in individuals with lower vitamin D status.

Table 2: Biochemical and Inflammatory Parameters According to Vitamin D Status. Significant at p < 0.05

Cognitive Function Outcomes

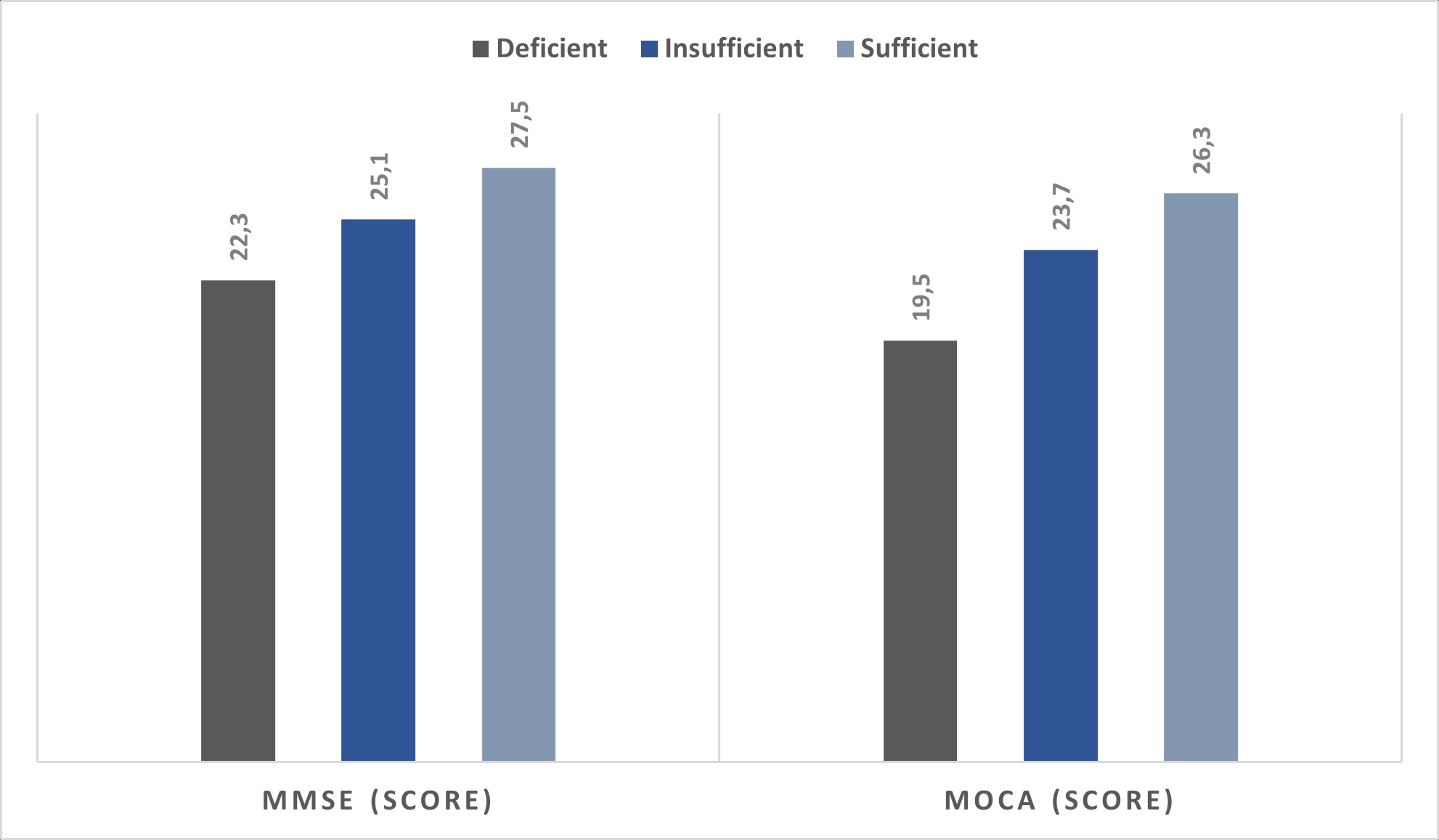

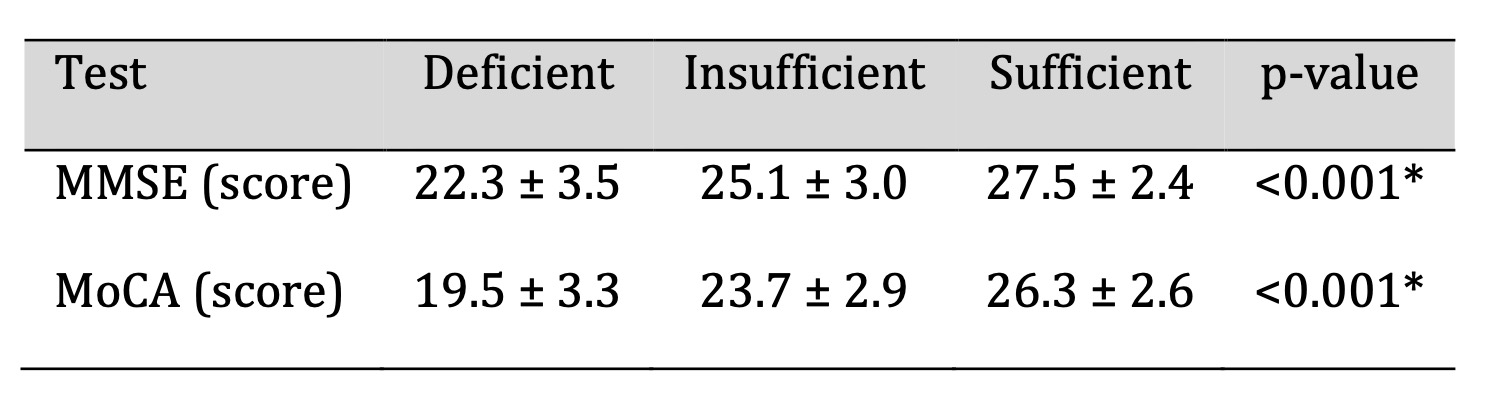

Cognitive performance, assessed using the MMSE and MoCA, was significantly lower

among

participants with vitamin D deficiency compared with those with sufficient levels

(Fig. 1).

As shown in Table 3, the mean MMSE score was 22.3 ± 3.5 in the deficient group and

27.5 ±

2.4 in the sufficient group (p < 0.001). A similar pattern was observed for MoCA

scores,

indicating that lower 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with reduced global

cognitive

function. These results demonstrate a significant relationship between vitamin D

status and

cognitive performance in older adults, suggesting that lower vitamin D levels may be

linked

to impairments in neurocognitive processes relevant to neuronal signalling.

Fig. 1: Cognitive Function Scores by Vitamin D Categories.

Table 3: Cognitive Function Scores by Vitamin D Categories. Significant at p < 0.05

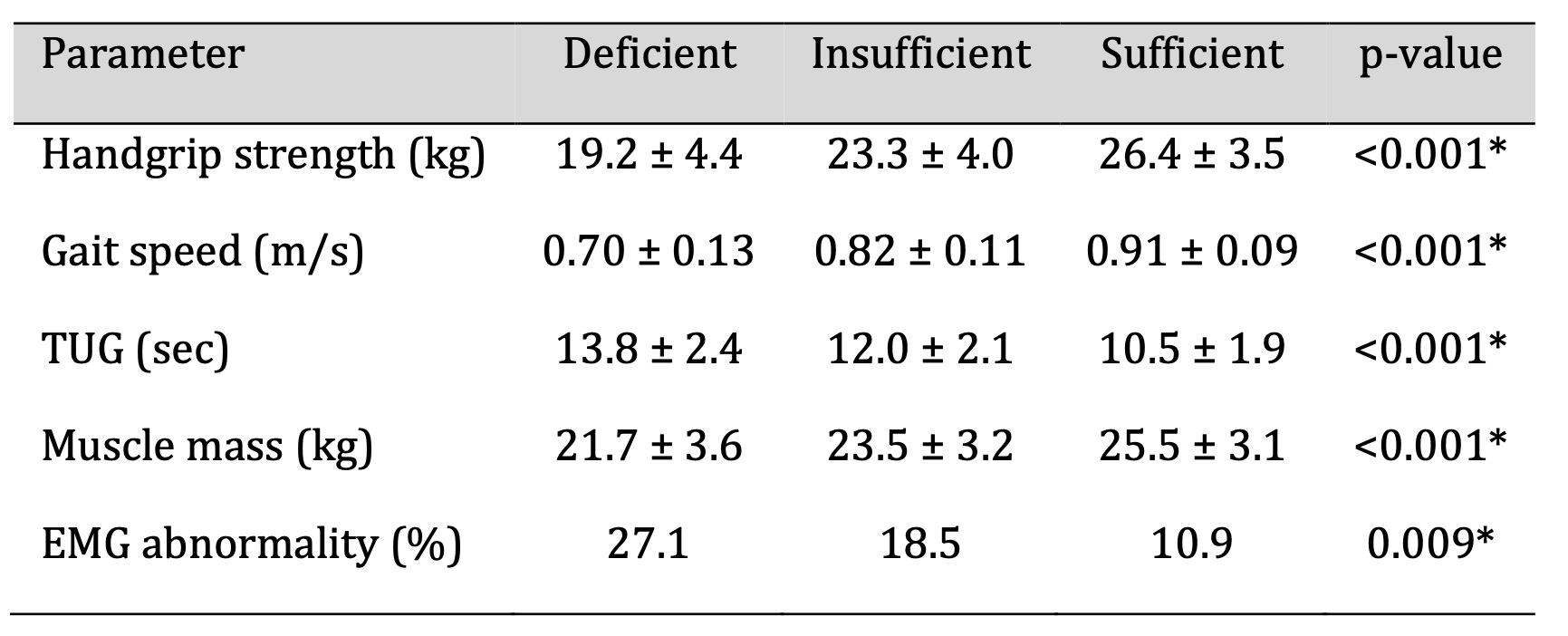

Neuromuscular Performance

As summarized in Table 4, participants with vitamin D deficiency exhibited

significantly

reduced neuromuscular performance compared with those with sufficient levels.

Deficient

individuals showed weaker handgrip strength and slower gait speed, along with

prolonged

Timed Up and Go (TUG) times (p < 0.001). Bioelectrical impedance analysis

revealed

decreased skeletal muscle mass, and electromyography (EMG) demonstrated a higher

frequency

of mild conduction delays suggestive of impaired neuromuscular transmission.

Overall,

neuromuscular performance declined progressively with lower 25(OH)D

concentrations. While

causality cannot be inferred, these findings indicate that vitamin D status is

closely

associated with functional measures relevant to neuromuscular signalling and

motor unit

integrity.

Table 4: Neuromuscular Function Parameters According to Vitamin D Levels. Significant at p < 0.05

Correlation Between Vitamin D and Biochemical, Cognitive, and

Neuromuscular

Parameters

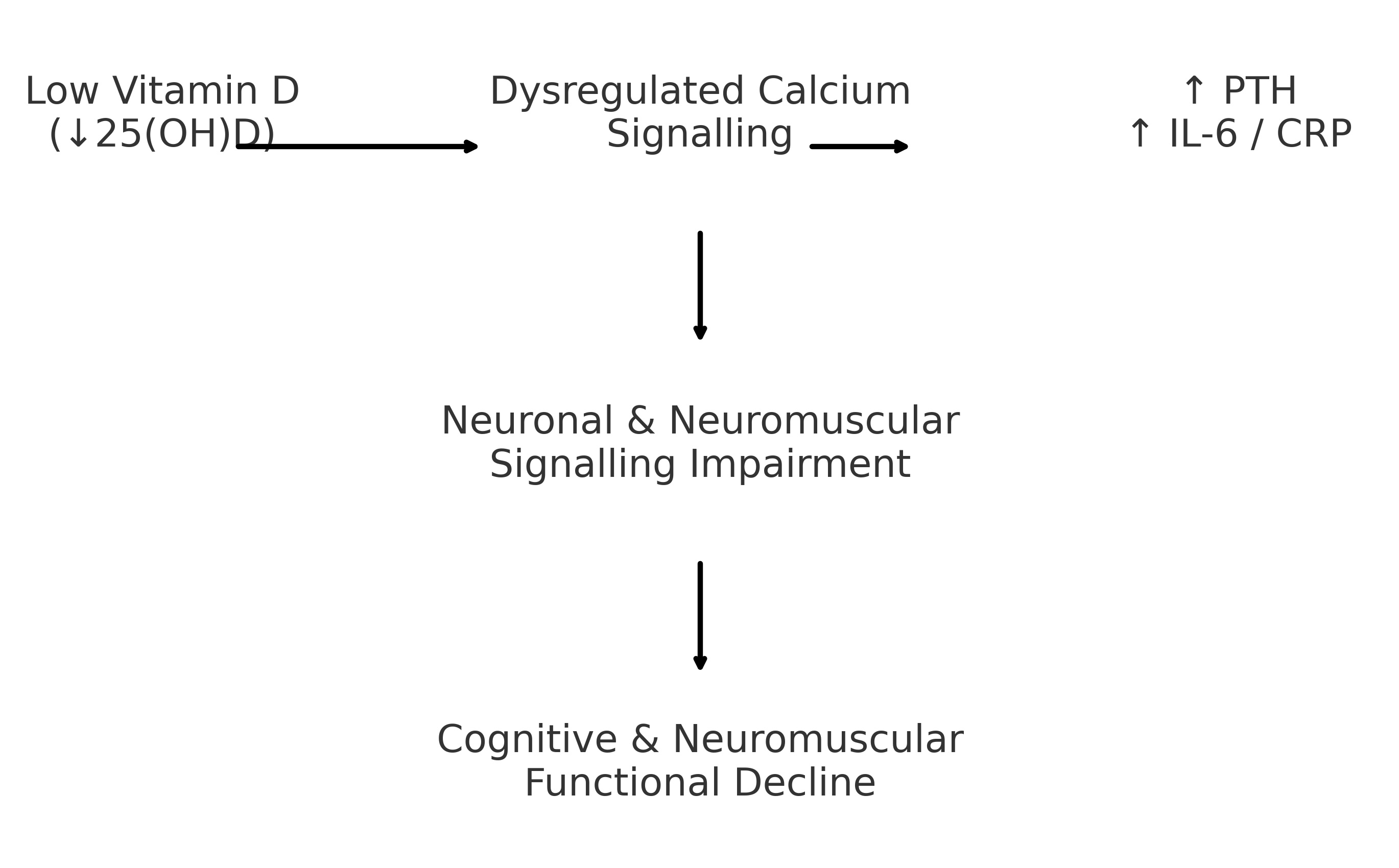

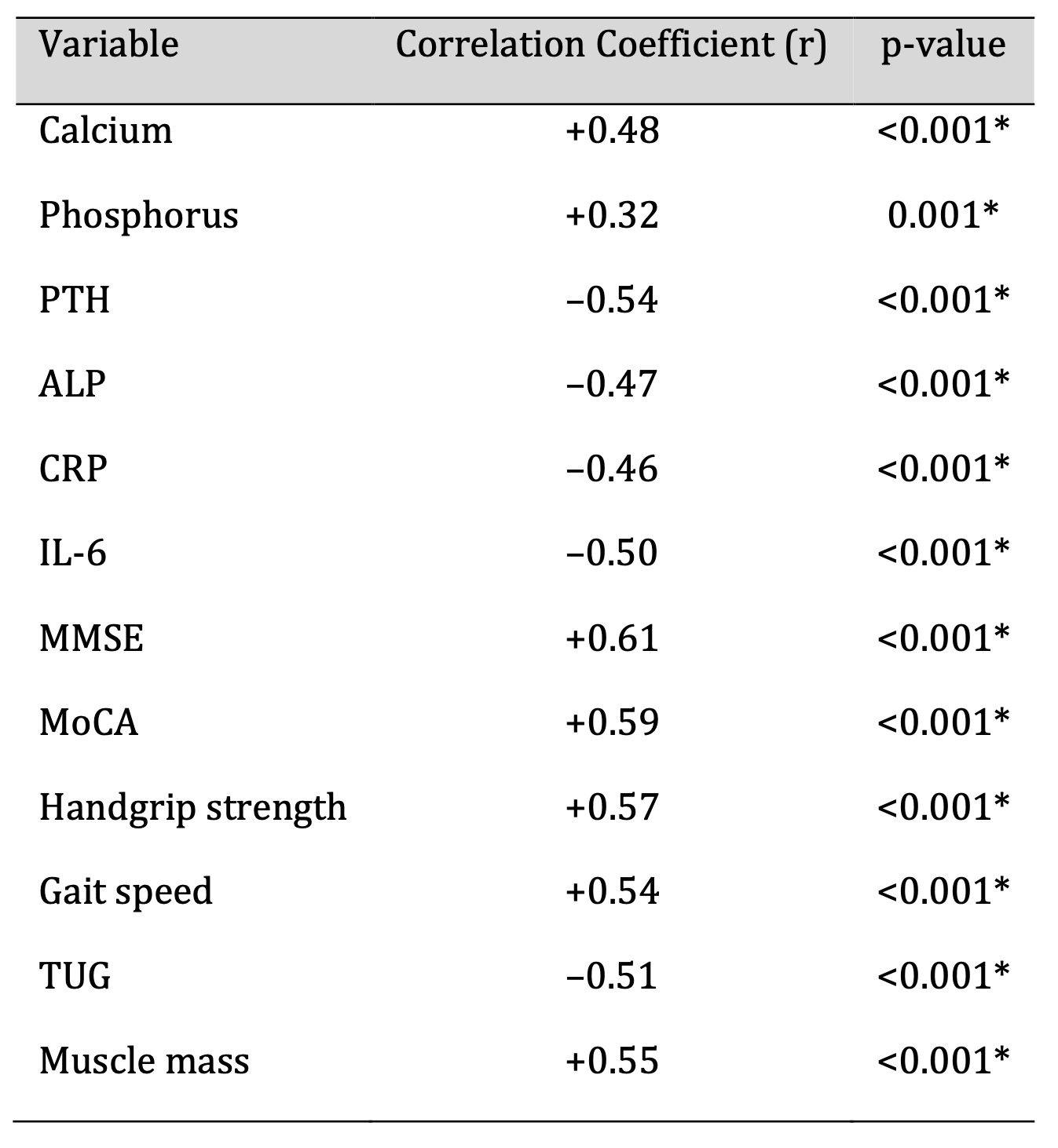

Pearson correlation analyses revealed several significant associations

between serum 25(OH)D

levels and key biochemical, cognitive, and neuromuscular measures (Table 5).

Vitamin D

concentrations were positively correlated with serum calcium, MMSE and MoCA

scores, handgrip

strength, gait speed, and skeletal muscle mass (p < 0.001). In contrast,

negative

correlations were observed between vitamin D levels and PTH, CRP, IL-6, and

TUG test time (p

< 0.001). These findings indicate that lower vitamin D status is

consistently associated

with altered calcium metabolism, heightened inflammatory signalling, and

reduced

neurocognitive and neuromuscular performance in older adults. A conceptual

model summarizing

these proposed mechanistic pathways is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2: Conceptual model illustrating the proposed pathways linking low vitamin D status to cognitive and neuromuscular dysfunction in older adults. Reduced serum 25(OH)D concentrations are associated with dysregulated calcium signalling and increased inflammatory activity (elevated PTH, IL-6, and CRP). These alterations may contribute to impaired neuronal and neuromuscular communication, potentially leading to cognitive decline, reduced muscle performance, and slower motor function.

Table 5: Correlation Between Serum Vitamin D and Study Parameters (n = 250). Significant at p < 0.05

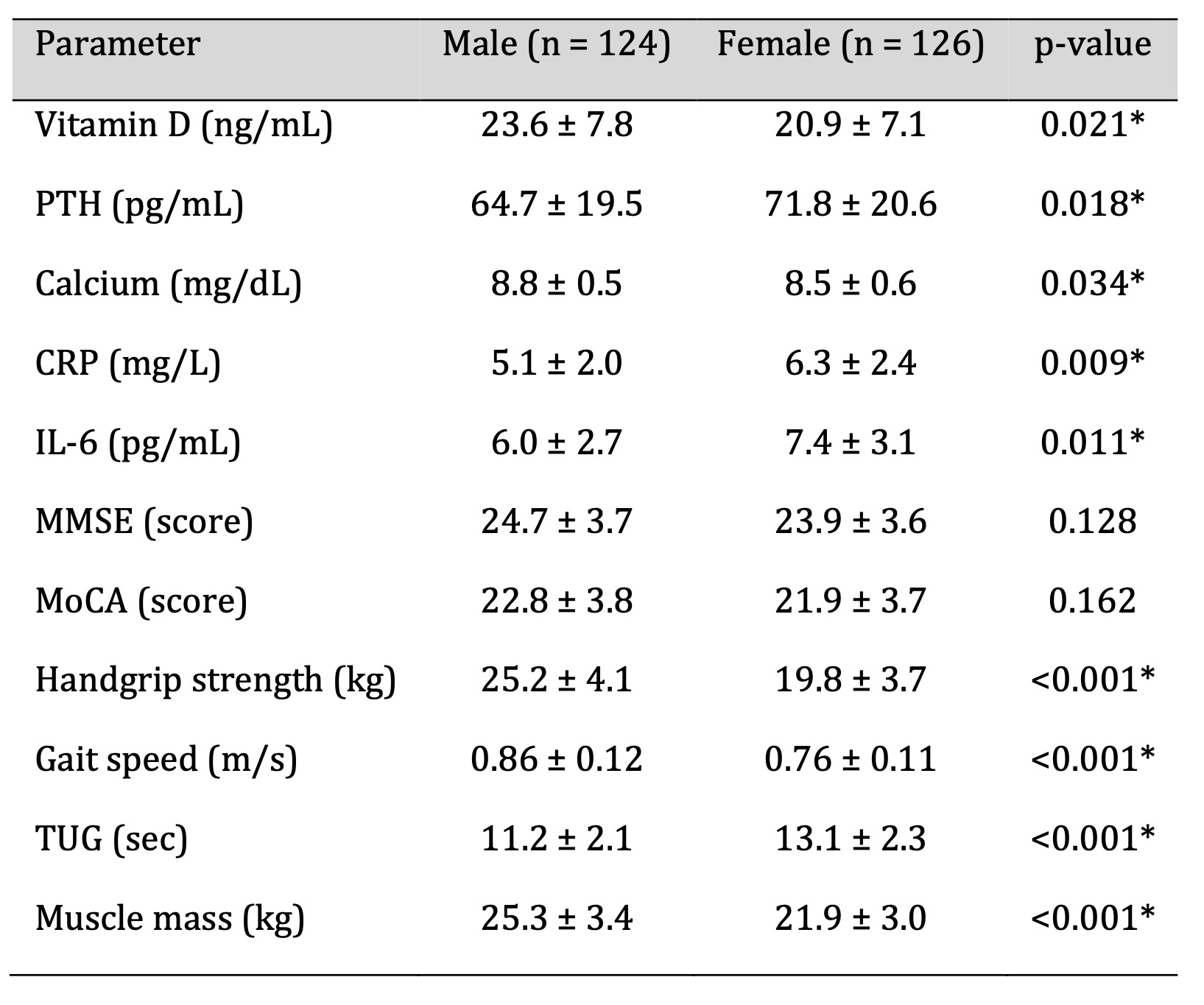

Gender-Based Comparison of Study Parameters

Sex-stratified analyses were conducted to examine potential differences

in vitamin D status

and associated functional measures. As shown in Table 6, men exhibited

significantly higher

serum 25(OH)D levels than women (23.6 ± 7.8 ng/mL vs. 20.9 ± 7.1 ng/mL,

p = 0.021). Male

participants also demonstrated higher handgrip strength, faster gait

speed, and greater

skeletal muscle mass, although some of these differences did not reach

statistical

significance (p > 0.05).

Women showed a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, elevated

inflammatory markers, and

lower neuromuscular performance. These patterns may reflect sex-specific

differences in sun

exposure, body composition, hormonal transitions after menopause, and

baseline muscle mass.

While mechanistic conclusions cannot be drawn from this cross-sectional

analysis, the

findings highlight that vitamin D status and its functional correlates

may vary by sex in

older adults. Such variation suggests the potential value of considering

sex-specific

factors when evaluating vitamin D–related neurocognitive and

neuromuscular outcomes in aging

populations.

Table 6: Comparison of Key Parameters Between Male and Female Participants (n = 250). Significant at p < 0.05

Discussion

This study demonstrated that lower serum 25(OH)D concentrations were associated with poorer cognitive performance, reduced neuromuscular function, and alterations in biochemical and inflammatory markers among older adults. Participants with vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/mL) exhibited significantly lower MMSE and MoCA scores compared with those with sufficient levels, consistent with findings from prior observational studies reporting similar associations between low 25(OH)D and impaired cognition [21, 22]. Mendelian randomization analyses have further suggested a potential directional association between genetically predicted vitamin D levels and cognitive outcomes, although firm causal inferences remain uncertain [23]. Experimental data supporting vitamin D’s role in neurotrophic signalling—including the regulation of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)—provide additional biological plausibility for these associations [24].

The presence of VDR and 1α-hydroxylase in the hippocampus, cortex, and other brain regions underscores vitamin D’s potential influence on neuronal signalling pathways involved in learning, memory, synaptic plasticity, and neurotransmission [25]. In this context, the cognitive findings observed in our cohort align with the broader literature suggesting that inadequate vitamin D status may adversely affect neurocognitive processes relevant to aging.

Our neuromuscular findings similarly showed that individuals with vitamin D deficiency had lower handgrip strength, slower gait speed, longer TUG times, reduced muscle mass, and a higher frequency of EMG abnormalities. These results are comparable to those of the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing and other cohorts reporting increased risk of reduced physical performance and frailty among individuals with low vitamin D levels [26, 27]. Because vitamin D participates in calcium flux in muscle cells, regulation of protein synthesis, and maintenance of neuromuscular junction integrity, deficiency may indirectly impair neuromuscular signalling and motor unit activation, although our cross-sectional design precludes causal interpretation.

Intervention trials of vitamin D supplementation have produced mixed results. Some randomized controlled trials reported no significant improvements in strength or physical performance despite increases in serum 25(OH)D [28]. Meta-analyses further suggest that supplementation may be beneficial primarily in individuals with severely low baseline levels and when combined with resistance training [29]. These inconsistencies imply that vitamin D may act as one component within a broader physiological network including physical activity, baseline muscle mass, comorbidities, and inflammatory status [30].

In our cohort, vitamin D deficiency was accompanied by reduced serum calcium, elevated PTH, and increased CRP and IL-6, reflecting dysregulated calcium homeostasis and heightened inflammatory signalling. These findings align with known physiological responses to hypovitaminosis D and are consistent with reports linking low 25(OH)D levels to increased systemic inflammation in older adults [31]. Elevated IL-6 and CRP have been independently associated with reduced muscle strength, diminished gait speed, and impaired cognitive function, supporting the possibility that inflammation serves as an intermediary pathway linking vitamin D status to neurocognitive and neuromuscular outcomes.

The combined profile of low vitamin D, secondary hyperparathyroidism, increased inflammatory activity, and decreased muscle mass suggests that functional impairments in deficient individuals are likely multifactorial rather than attributable to vitamin D alone. The interplay between altered calcium signalling, neuroinflammatory activity, and sarcopenia may collectively contribute to deficits in neuronal and neuromuscular communication.

Sex-stratified analyses revealed that men had higher 25(OH)D levels and generally better neuromuscular performance than women. Women also exhibited greater inflammatory burden and a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency. These findings are consistent with known differences in sun exposure, body composition, and hormonal changes following menopause, which can influence vitamin D metabolism and musculoskeletal health [32]. Such sex-specific variations may help explain some heterogeneity observed in supplementation trials and highlight the need for gender-sensitive approaches to screening and intervention.

Overall, our findings contribute to a growing body of evidence suggesting that vitamin D status is associated with neurocognitive performance, neuromuscular function, and key biochemical pathways involved in neuronal and muscular signalling. Longitudinal and interventional studies are needed to clarify causal mechanisms and to determine whether strategies targeting vitamin D insufficiency could help preserve neurophysiological function in aging populations.

Conclusion

This study identified significant associations between lower serum 25(OH)D concentrations and diminished cognitive and neuromuscular performance in older adults aged 65–85 years in Tikrit City. Individuals with vitamin D deficiency demonstrated poorer scores on MMSE and MoCA, reduced handgrip strength, slower gait speed, lower muscle mass, and elevated TUG times. These functional deficits coincided with increased inflammatory marker levels and higher PTH concentrations, suggesting that disturbances in calcium homeostasis, heightened inflammatory signalling, and potential impairments in neuromuscular transmission may contribute to the observed decline in neurocognitive and neuromuscular function.

Sex-specific differences were also noted, with women exhibiting lower vitamin D levels, higher inflammatory burden, and reduced neuromuscular performance. This highlights the importance of considering biological and lifestyle factors that differentially affect men and women in later life.

Although the cross-sectional nature of the study precludes causal inference, the coherence of biochemical, cognitive, and neuromuscular findings supports the hypothesis that vitamin D status plays a role in physiological pathways relevant to neuronal and neuromuscular signalling. Longitudinal and interventional studies are warranted to determine causality, clarify underlying mechanisms, and establish evidence-based strategies for vitamin D optimization aimed at preserving neurophysiological function in aging populations.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be considered when

interpreting the findings.

First, its cross-sectional design does not allow causal inferences

regarding the

relationship between vitamin D status and cognitive or neuromuscular

function. Longitudinal

and interventional studies are required to determine whether

optimizing vitamin D levels can

directly influence neurophysiological outcomes. Second,

electromyography was performed only

in a subgroup of participants, which may limit the generalizability

of observations related

to neuromuscular transmission. Third, unmeasured confounders—such as

detailed nutritional

intake, physical activity patterns, or sunlight exposure—may have

influenced both vitamin D

status and functional performance. Fourth, neuroimaging and advanced

neurophysiological

biomarkers (e.g., cortical excitability, neurotransmitter levels)

were not assessed, which

restricts deeper mechanistic interpretation. Finally, the study

population was drawn from a

single regional hospital, and cultural or environmental factors

specific to this setting may

not fully represent broader aging populations. Despite these

limitations, the coherence of

biochemical, cognitive, and neuromuscular findings provides a

valuable foundation for future

mechanistic and interventional research.

Recommendations

From a clinical perspective, our findings support the consideration

of routine vitamin D

screening in older adults—particularly those aged 65–85 years,

individuals with metabolic

comorbidities such as hypertension or diabetes, women, and those

with limited sun exposure.

Identifying and correcting vitamin D deficiency through

supplementation, structured sunlight

exposure, and dietary guidance may contribute to maintaining

cognitive and neuromuscular

health, especially when combined with resistance training, physical

activity programs, and

management of inflammatory and cardiometabolic risk factors.

Future randomized controlled trials in older Middle Eastern

populations should evaluate

multicomponent interventions that integrate vitamin D

supplementation with structured

exercise and inflammation-modulating strategies. Establishing

population-appropriate serum

thresholds for intervention (e.g., >30–50 ng/mL) may improve the

ability to target

individuals at risk for neurocognitive and neuromuscular decline.

Mechanistic studies are also needed to investigate VDR expression

and activity in neural and

muscular tissues, the role of neuroinflammatory pathways, and the

molecular cross-talk

between bone, muscle, and brain. Such work may clarify how vitamin D

influences neuronal

signalling and neuromuscular function and help guide interventions

to support healthy aging.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

| 1 | Verstuyf, A., Carmeliet, G., Bouillon, R., & Mathieu, C.

(2010). Vitamin D: A

pleiotropic hormone. Kidney International, 78(2),

140-145.

https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.17

https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2010.17 |

| 2 | Anderson, P. H., Turner, A. G., & Morris, H. A. (2012).

Vitamin D acts to

regulate calcium and skeletal homeostasis. Clinical

Biochemistry, 45(12),

880-886.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.02.020

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2012.02.020 |

| 3 | Liu, Y., Wang, W., Yang, Y., et al. (2025). Vitamin D

and bone health: From

physiological function to disease association. Nutrition

& Metabolism, 22, 113.

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-025-01011-1

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12986-025-01011-1 |

| 4 | Pike, J. W., Zella, L. A., Meyer, M. B., Fretz, J. A., &

Kim, S. (2007).

Molecular actions of 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D₃ on genes

involved in calcium

homeostasis. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research,

22(Suppl 2), V16-V19.

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.07s207

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.07s207 |

| 5 | Holick, M. F. (2008). Deficiency of sunlight and vitamin

D. BMJ, 336(7657),

1318-1319. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39581.411424.80

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39581.411424.80 |

| 6 | El-Mallah, C., Yarparvar, A., Galetti, V., Obeid, O.,

Boutros, M., Safadi, G.,

ZeinEddine, R., Ezzeddine, N. E. H., Kouzeiha, M.,

Kobayter, D., Wirth, J. P.,

Abi Zeid Daou, M., Asfahani, F., Hilal, N., Hamadeh, R.,

Abiad, F., & Petry, N.

(2025). The sunshine paradox: Unraveling risk factors

for low vitamin D status

among non-pregnant women in Lebanon. Nutrients, 17(5),

804.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050804

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17050804 |

| 7 | Gallagher, J. C., & Sai, A. J. (2010). Vitamin D

insufficiency, deficiency, and

bone health. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology &

Metabolism, 95(6), 2630-2633.

https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-0918

https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2010-0918 |

| 8 | De Martinis, M., Allegra, A., Sirufo, M. M., Tonacci,

A., Pioggia, G.,

Raggiunti, M., Ginaldi, L., & Gangemi, S. (2021).

Vitamin D deficiency,

osteoporosis, and effect on autoimmune diseases and

hematopoiesis: A review.

International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(16),

8855.

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168855

https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22168855 |

| 9 | Laird, E., Ward, M., McSorley, E., Strain, J. J., &

Wallace, J. (2010). Vitamin

D and bone health: Potential mechanisms. Nutrients,

2(7), 693-724.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2070693

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu2070693 |

| 10 | Wang, Q., Yu, D., Wang, J., & Lin, S. (2020).

Association between vitamin D

deficiency and fragility fractures in Chinese elderly

patients: A

cross-sectional study. Annals of Palliative Medicine,

9(4), 1785-1792.

https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-610

https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-19-610 |

| 11 | Ceglia, L. (2009). Vitamin D and its role in skeletal

muscle. Current Opinion in

Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care, 12(6), 628-633.

https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707

https://doi.org/10.1097/MCO.0b013e328331c707 |

| 12 | Agoncillo, M., Yu, J., & Gunton, J. E. (2023). The Role

of Vitamin D in Skeletal

Muscle Repair and Regeneration in Animal Models and

Humans: A Systematic Review.

Nutrients, 15(20), 4377.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204377

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15204377 |

| 13 | Yin, K., & Agrawal, D. K. (2014). Vitamin D and

inflammatory diseases. Journal

of Inflammation Research, 7, 69-87.

https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S63898

https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S63898 |

| 14 | Fenercioglu, A. K. (2024). The anti-inflammatory roles

of vitamin D for

improving human health. Current Issues in Molecular

Biology, 46(12),

13514-13525. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120807

https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb46120807 |

| 15 | Sultan, S., Taimuri, U., Basnan, S. A., Al-Orabi, W. K.,

Awadallah, A.,

Almowald, F., & Hazazi, A. (2020). Low vitamin D and its

association with

cognitive impairment and dementia. Journal of Aging

Research, 2020, 6097820.

https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6097820

https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6097820 |

| 16 | Łukaszyk, E., Bień-Barkowska, K., & Bień, B. (2018).

Cognitive functioning of

geriatric patients: Is hypovitaminosis D the next marker

of cognitive

dysfunction and dementia? Nutrients, 10(8), 1104.

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081104

https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10081104 |

| 17 | Ates Bulut, E., Soysal, P., Yavuz, I., Kocyigit, S. E.,

& Isik, A. T. (2019).

Effect of vitamin D on cognitive functions in older

adults: 24-week follow-up

study. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other

Dementias, 34(2),

112-117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317518822274

https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317518822274 |

| 18 | Al-Mohaimeed, A., Khan, N. Z., Naeem, Z., & Al-Mogbel,

E. (2012). Vitamin D

status among women in the Middle East. Journal of Health

Science, 2(6), 49-56.

https://doi.org/10.5923/j.health.20120206.01

|

| 19 | Faisal Ghazi, H., Mohammed Jwad Taher, T., & Nezar

Hasan, T. (2024). Knowledge

about vitamin D among the general population in Baghdad

City. Rwanda Journal of

Medical and Health Sciences, 7(1), 89-100.

https://doi.org/10.4314/rjmhs.v7i1.7

https://doi.org/10.4314/rjmhs.v7i1.7 |

| 20 | Lips, P., de Jongh, R. T., & van Schoor, N. M. (2021).

Trends in vitamin D

status around the world. JBMR Plus, 5(12), e10585.

https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10585

https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10585 |

| 21 | Llewellyn, D. J., Lang, I. A., Langa, K. M., & Melzer,

D. (2011). Vitamin D and

cognitive impairment in the elderly U.S. population.

Journal of Gerontology:

Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences,

66(1), 59-65.

https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq185

https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq185 |

| 22 | Li, P. Y., Li, N. X., & Zhang, B. (2024). Vitamin D and

cognitive performance in

older adults: A cross-sectional and Mendelian

randomization study. Alpha

Psychiatry, 25(3), 323-328.

https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2024.231486

https://doi.org/10.5152/alphapsychiatry.2024.231486 |

| 23 | Quialheiro, A., d'Orsi, E., Moreira, J. D., Xavier, A.

J., & Peres, M. A.

(2023). The association between vitamin D and BDNF on

cognition in older adults

in Southern Brazil. Revista de Saúde Pública, 56,

Article 6.

https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2022056004134

https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2022056004134 |

| 24 | Ruscalleda, R. M. I. (2023). Vitamin D - Physiological,

nutritional,

immunological, genetic aspects: Actions in autoimmune,

tumor, and infectious

diseases; musculoskeletal and cognitive functions.

Revista de Medicina (São

Paulo), 102(3), e-210547.

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1679-9836.v102i3e-210547

https://doi.org/10.11606/issn.1679-9836.v102i3e-210547 |

| 25 | Toffanello, E. D., Coin, A., Perissinotto, E., Zambon,

S., Sarti, S., Veronese,

N., De Rui, M., Bolzetta, F., Corti, M. C., Crepaldi,

G., Manzato, E., & Sergi,

G. (2014). Vitamin D deficiency predicts cognitive

decline in older men and

women: The Pro. V.A. study. Neurology, 83(24),

2292-2298.

https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001080

https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0000000000001080 |

| 26 | Aspell, N., Laird, E., Healy, M., Lawlor, B., &

O'Sullivan, M. (2019). Vitamin D

deficiency is associated with impaired muscle strength

and physical performance

in community-dwelling older adults: Findings from the

English Longitudinal Study

of Ageing. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 14,

1751-1761.

https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S222143

https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S222143 |

| 27 | Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (UK). (2011).

Effect of vitamin D

supplementation on muscle strength: A systematic review

and meta-analysis. In

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE):

Quality-assessed Reviews.

University of York.

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK80810/

|

| 28 | Houston, D. K., Marsh, A. P., Neiberg, R. H., Demons, J.

L., Campos, C. L.,

Kritchevsky, S. B., Delbono, O., & Tooze, J. A. (2023).

Vitamin D

supplementation and muscle power, strength, and physical

performance in older

adults: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal

of Clinical Nutrition,

117(6), 1086-1095.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.04.021

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajcnut.2023.04.021 |

| 29 | Vaes, A. M. M., Brouwer-Brolsma, E. M., Toussaint, N.,

et al. (2019). The

association between 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration,

physical performance, and

frailty status in older adults. European Journal of

Nutrition, 58, 1173-1181.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1634-0

https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-018-1634-0 |

| 30 | Yang, A., Lv, Q., Chen, F., Wang, Y., Liu, Y., Shi, W.,

Liu, Y., & Wang, D.

(2020). The effect of vitamin D on sarcopenia depends on

the level of physical

activity in older adults. Journal of Cachexia,

Sarcopenia and Muscle, 11(3),

678-689. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12545

https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12545 |

| 31 | Silverberg, S. J. (2007). Vitamin D deficiency and

primary hyperparathyroidism.

Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 22(Suppl. 2),

V100-V104.

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.07s202

https://doi.org/10.1359/jbmr.07s202 |

| 32 | Roth, D. E., Abrams, S. A., Aloia, J., Bergeron, G.,

Bourassa, M. W., Brown, K.

H., Calvo, M. S., Cashman, K. D., Combs, G., De-Regil,

L. M., Jefferds, M. E.,

Jones, K. S., Kapner, H., Martineau, A. R., Neufeld, L.

M., Schleicher, R. L.,

Thacher, T. D., & Whiting, S. J. (2018). Global

prevalence and disease burden of

vitamin D deficiency: A roadmap for action in low- and

middle-income countries.

Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1430(1),

44-79.

https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13968

https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13968 |